Director – Homayoun Ghanizadeh – 2025 – Iran, USA, France, Canada – 107m

*****

On a video phone network, a woman is caught between her well-off family and their former servant’s wronged son – premieres in the Critics’ Picks Competition of the 29th Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival

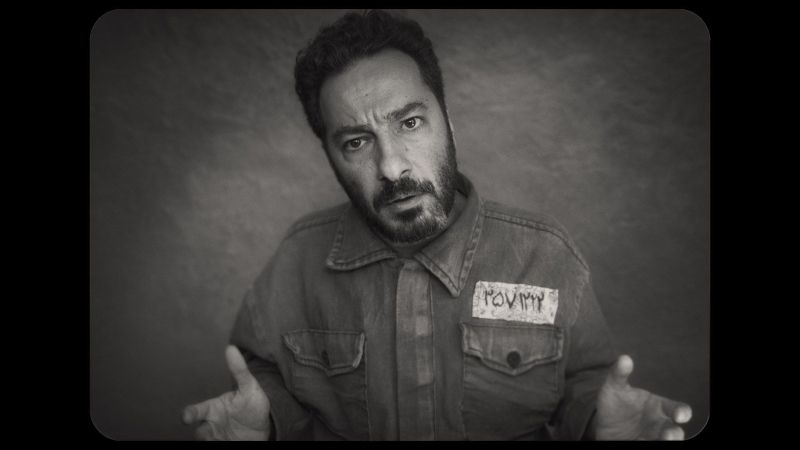

Facing us, photographed in black and white, an old man hangs up, revealed by his offline screen to be Mr. Farrokhi (Ali Nassirian) in Los Angeles, as a woman rails to camera, hurling obscenities at him as at the viewer. Her screen enlarges as it moves to centre screen. He and she, like the other characters who appear in this drama, is wearing what looks like a prison uniform with a designation tab above the right breast.

As the piece proceeds, you start to get a handle on the ground rules: this is a film that owes much to communications technologies like Zoom. Characters only ever appear here within a Zoom type box in black and white, slowly morphing into colour for moments when they relax or are less guarded and more openly themselves. Sometimes there is only a single box with its one character filling the screen; this shifts to two, three – or, in two rows, four or five – boxes side by side. The five characters appear and disappear throughout and their comms boxes change size and move around the screen as they contact each other on this screen-based comms network.

Zoom rose to prominence during the year 2000 global pandemic when societies were, quite literally, locked down and people were trapped alone or in pairs in their homes. While there have been a number of movies that have tried to deal directly with life during the pandemic, this is not actually one of those films. Although it’s true that we only ever see each of the five characters in a screen box, there are references to characters being able to do things outside of their homes, with one character trying to sort out a legal matter with one of the others relating to property prior to attending a court hearing the next day. There is no suggestion as such that these characters can’t go outside their homes and interact in society. Except those uniforms,which are the first thing you notice, and which suggest that the whole of the society, which we only see through its video telephony users’ call screens, is a giant prison.

There is, however, a suggestion that the society is, in some other sense, locked down. One way or another, these characters, in their various positions in Iranian society which has undeniably undergone a radical shift since the 1979 Revolution, are all trapped, as the outburst of the woman at the start suggests. Even Mr. Farroukhi, who has got out of Iran to Los Angeles, appears trapped in a prison – of his own greed and spitefulness.

The plot goes something like this: A woman, Homa (Golshifteh Farahani from My Father’s Dragon, Nora Twomey, 2022; Paterson, Jim Jarmusch, 2016; Eden, Mia Hansen-Løve, 2014; Rosewater, Jon Stewart, 2014), is contacted from Tehran, 12 hours from her, by Mr. Hashemi (Navid Mohammadzadeh from Law of Tehran, Saeed Roustayi, 2019), the son of her family’s former servant, who wants to resolve a legal problem, specifically that he bought the house off his former employer, because if he can’t prove this then the property will be taken off him by the state. Your initial sympathy for him diminishes to an extent when you realise that he is not actually living there, that this is an additional property to his everyday home, so losing it wouldn’t make him homeless.

Nevertheless, you have a degree of sympathy for him, given that Mr. Farrokhi is sending his lawyer to the court to deny Mr. Hashemi’s ownership of the property: there was a document that the patriarch allegedly signed, but claims the signature was forged. If Mr. Farrokhi himself can’t retain the property, he doesn’t see why anyone else should have it.

Rather than go direct to Mr. Farrokhi, Mr. Hashemi is going firstly via Homa and then via her aunt Mrs. Khosravi (Shirin Neshat), the patriarch’s daughter, feeling that the two of them, particularly the aunt, may be able to put in a good word for him, thus enabling him to achieve his desired outcome. Homa and Mrs. Khosravi also bring Homa’s uncle / Mrs. Khosravi’s brother Mr. Nader (Payman Maadi from Law of Tehran, 2017; A Separation, Asghar Farhadi, 2011). Mr. Farroukhi’s third child Iraj, (who we never see), Homa’s father, was taken away by the state years ago, and it turns out that Mr. Hashemi’s father, the family servant, long since deceased, framed him.

The motives of various characters are complicated, but relate to sexual improprieties which emerge as Mr. Hashemi confront Mr. Farrokhi. It turns out that the former has something on Homa, specifically a video of her which he has so far not put online where it would almost certainly go viral. If he doesn’t get his own way and retain the property – which looks likely given Mr. Farrokhi’s spiteful nature – then Mr. Hashemi will release the video which will probably ruin Homa’s life.

It’s a bleak picture of both of a repressive society of haves and have-nots, where former elites have got out before those they oppressed have had the chance to turn the tables on them, and one in which people within and without are desperately unhappy protecting or advancing their social status. A as radical reinvention of cinema, finding a new way of using the medium to tell its story, it’s peerless. The jewel in the crown of this year’s Critics’ Picks programme, it deserves wider international distribution even more than the other films in competition.

Oh, What Happy Days! premieres in the Critics’ Picks Competition of the 29th Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival which runs in cinemas from Friday, November 7th to Sunday, November 23rd 2025.

Trailer:

Critics’ Picks mashup trailer:

Festival teaser trailer: