Director – Takahide Hori – 2021 – Japan – Cert. 15 – 101m

****1/2

A cyborg is dropped from the planet’s surface into its depths by his immortal but impotent masters to investigate the beings who have evolved in the levels below – feature length, stop-frame epic is out in UK cinemas on Monday, April 24th

More, I suspect, by accident than design, Junk Head looks and feels like the wandering little sister of Mad God (Phil Tippett, 2021). The latter was made by a top Hollywood stop-frame effects animator as a 34-year, independent, labour of love, the former by a Japanese visionary as a seven-year, independent, labour of love. Hori had worked on puppetry at Tokyo Disneyland and became obsessed with stop-motion, inspired by Motoko Shinkai’s one-man debut 2D animated production Voices of A Distant Star (2002). He made a half hour version Junk Head 1 in 2013, and used it as a building block to this version, which he completed in 2017.

The production mode of stop-frame can be a solitary one involving one person alone in a room with a camera and armatured puppets, the approach typified by Willis O’Brien, Ray Harryhausen, the bolexbrothers, Jiri Trnka, Kihachiro Kawamoto, the early David Lynch and many others – a single person or very small number of people producing the work, either complete films or stop-frame effects sequences within live action films. (Phil Tippett is something of an exception in that he built a heavyweight effects company to deliver stop-frame sequences in bulk for other people’s movies, for which he eventually switched from stop-frame to CGI, but his work never stopped feeling like stop-frame.)

The result with such films (or effects sequences) is that they are heavily auteurist – the director-animator (often, as in Hori’s case, the writer-director-animator) exerts considerable control over the final result. It’s a very slow process in which they impart life to their 3D creations via the camera one frame at a time. As a result, the medium has a precision about it not found in other forms of filmmaking.

And so to Junk Head‘s plot.

The surface dwellers drop a cyborg in a capsule from a platform high up on a building in an urban landscape of tall buildings. Below them are various underground levels, where dangerous wild creatures roam free and small, crack squads of hunters track them down and destroy them. One such squad spots the descending capsule and shoots it down, causing capsule and cyborg to be scattered into pieces.

(Although the surface dwellers initiate the narrative, and are later revealed as incarcerated within their homes and heavily reliant on technology, with outside views of an unspoiled world customisable at the flick of a switch and all interaction conducted over computer video links in the manner of Zoom, the main story isn’t about them so much as about the cyborg and what happens to him. Given that Hori finished the film in 2017, this element can be seen as prophetic of what subsequently happened in the global pandemic lockdown.)

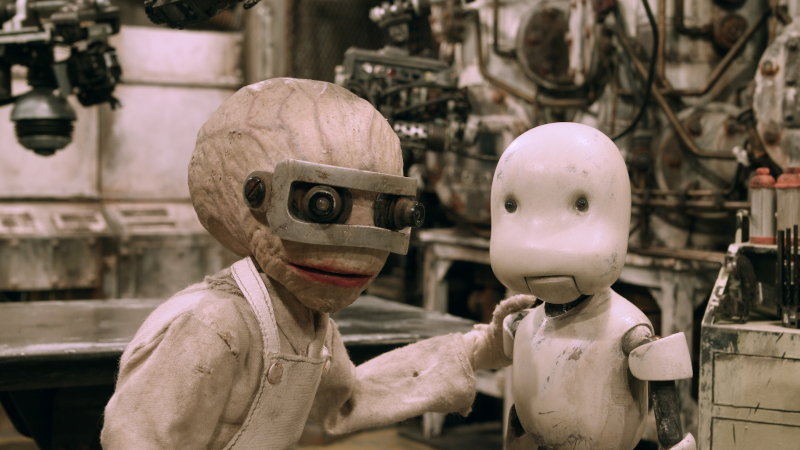

The junk head (as we shall call him) is found by a worker berated for collecting junk and finds its way to a boffin named the doctor, who builds it into a new body and sends it out to work with his team of diminutive scavengers. He keeps wandering off in a labyrinth of corridors where the perils in the form of various wild creatures, including some who resemble H.R. Giger’s designs for Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), and others who look like the carnivorous worms at the bottom of the ravine cut from King Kong (effects: Willis O’Brien, 1933) and put back in Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake, here modified for labyrinth life by the additional ability to tunnel through walls. A chance encounter with a wild creature triggers the junk head’s memory that his mission is to investigate such creatures, and puts him in conflict with his current hosts.

He is later pulled apart by the worms and his constituent parts kicked over a ledge to fall to a lower level still for reconstitution in a completely different body (which cannot speak, only understand and follow instructions). He is sent on a quest to collect some fresh food, which journey involves a communal lift platform operated by a being sitting on a fixed rig like a biker on a motorcycle and a fellow passenger who seeks to take advantage of him on his way back by conning him out of the food he is carrying.

Although a Japanese film, the dialogue is mostly mumbo jumbo with subtitles added, so you can follow what’s going on. (The film has been subtitled for different international territories, including Japan). As you can probably tell from my perfunctory summary above, plot isn’t the film’s strong point, yet it remains compelling throughout, driven by its extraordinary collection of strange worlds, societies, technologies, sentient populations and its menagerie of dangerous creatures preying on the unwary. It may not push the technical envelope quite as much as the dialogue-free Mad God, but it remains undeniably impressive and succeeds for many of the same reasons, i.e. a quest into depths and strange worlds by which we’re fascinated and about which we want to know more.

To say Junk Head resembles Mad God wouldn’t be entirely fair: although both films are about a character descending into strange and perilous depths, the downwards journey in Mad God at least allows its protagonist to disembark safely before his adventures begin; In Junk Head, the protagonist has no such chance and gets pulled apart and rebuilt each time he descends. However the worlds into which they descend, and the beings and creatures therein, are very different, so much so that neither film feels like a retread of the other outside of the broadest, synoptic outline. If you loved one, you will love the other.

Junk Head is out in cinemas in the UK on Monday, April 24th.

Trailer: