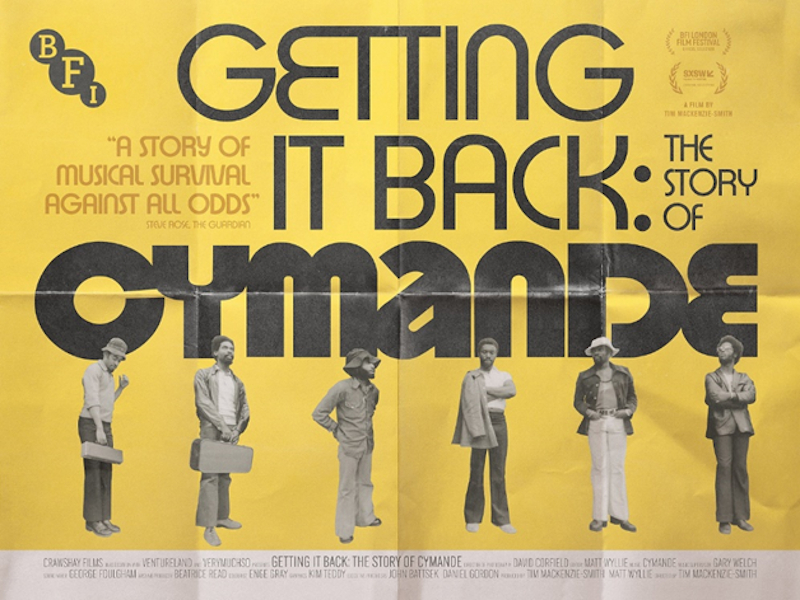

Director – Tim MacKenzie-Smith – 2022 – UK – Cert. 12a – 90m

****

How a promising, innovative black 1970s band failed to crack the UK music business, only for their music to take on a life of its own through various later, popular musical movements – out in UK cinemas on Friday, February 16th and out on BFI Blu-ray, BFI Player Subscription, iTunes and Amazon Prime on Monday, 26 February

Film critics have their blind spots (there are films you’d assume I’ve seen which I never have) and so too do serious music listeners, among whom I number myself. Prior to this film, I had never heard of Cymande. That’s surprising to me, actually, because I started seriously listening to music in the 1970s and have never stopped (although, significantly, rap and hip-hop, which came later, never really did it for me). And Cymande, it turns out, were a band of the early 1970s. It’s not mentioned in this film, but they played a couple of sessions for legendary UK Radio One DJ John Peel where it’s likely I would have heard them, had I started listening regularly to his show earlier than 1974, after they recorded a session.

The narrative in MacKenzie-Smith’s documentary runs something like this: in the 1950s and 60s, Britain invited numerous Commonwealth citizens from Caribbean islands like Jamaica, St. Vincent and Guyana to come over. When they arrived, however, they were confronted by racism and people who wanted Britain to be kept for white people. Music seemed to be one of the few avenues through which black people could succeed in the UK.

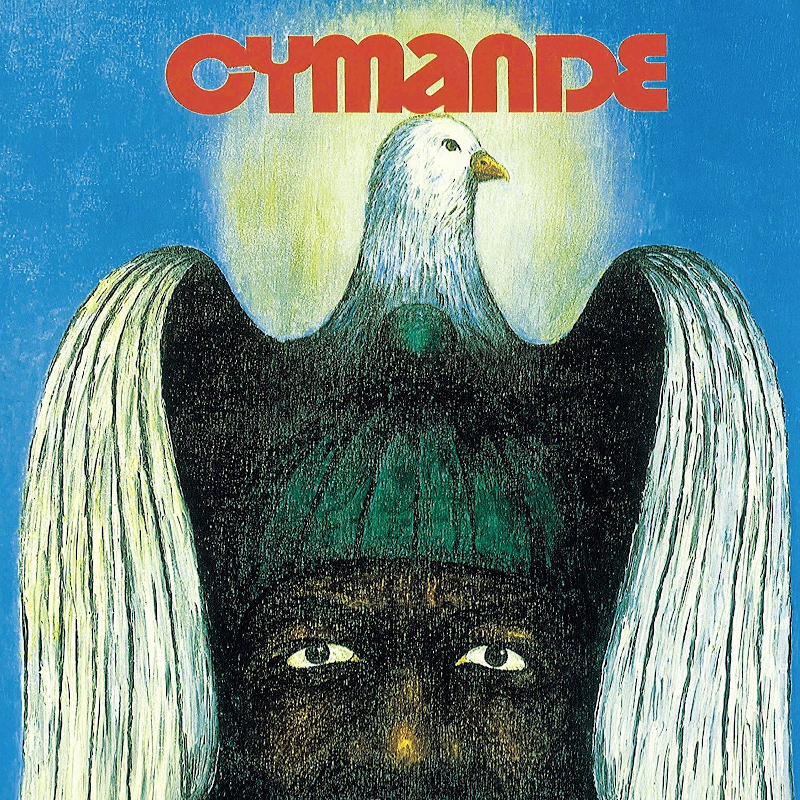

So, in 1971, Steve Scipio and Patrick Patterson formed Cymande in South London, soon expanding to about ten musicians from Brixton and Tooting. They played their own unique mix of musical influences – US soul, jazz, reggae and rock, a mix quite unlike anything else at the time. Discovered by music producer John Schroeder, they cut a deal with US record label Janus, for whom they ultimately recorded three LPs, and toured that country supporting legendary soul singer Al Green. But on return to Britain, they hit a wall. Faced with an institutionally racist UK record business, they took a break in 1975. They didn’t intend it to be a long break, but in the event it lasted 40 years.

Around the same time as the band split up, on the other side of the Atlantic, New York’s South Bronx district gave rise to DJ culture, and Cymande’s song Bra, with its danceable bass break passage, got a lot of play in the clubs. Some of those present in this movement themselves became producers and DJs within the next decade, and as the likes of De La Soul, M C Solaar, Masta Ace and The Fugees sampled Cymande, introducing the music to a wider audience which knew the music but not the band’s name. Crate diggers, as those who searched through boxes of records are known, would search for the records from which their DJs played or their artists sampled material, and the Cymande records became much sought after items.

Weirdly, once the film gets through its opening section of maybe half an hour, on Cymande’s story up to the point they split up, the subject of British racism seems to dissipate. Now, I have no wish or reason to disagree that Britain in the 1960s was (and today arguably still is to a lesser degree) racist or that racism may have been a factor preventing Cymande’s rise to the top. And clearly, they struck a chord with New York’s early rappers and hip-hop DJs who, as it were, picked up and carried Cymande’s voice into pop culture so that their music became, in time, a genuine, culturally significant phenomenon. One should add that, as presented in this documentary, these New York DJs included people of both black and white ethnicities, so what happened in the US was by no means a solely black phenomenon, more of a multi-racial one.

And now that I’ve finally heard Cymande’s music for myself, I’m a convert. On the evidence of excerpts from their 1970s recordings, and from watching footage of the band play live following their coming back together in 2015, they were then and are now a terrific band.

However, as a listener to a great many British musical acts from the seventies, I would like to offer an alternative explanation for why, at least in part, Cymande never made it. Countless, equally impressive British-based bands or musicians never achieved the stardom and success of those few acts that became household names in that decade. Many, like Cymande, demonstrated an admirable degree of musicianship, had a grassroots following from touring the UK’s pubs and clubs, and got as far as playing a session or two for John Peel, going on to make a handful or so of excellent albums.

Nevertheless, in Cymande’s and in many other’s cases, financial success eluded them for years. The lack of success of such acts may have had less to do with racism and more to do with a conservative (with a small ‘c’) UK record industry largely afraid to take chances on anything that was different. The industry picked acts it believed it could sell. (Sometimes it guessed right, sometimes it guessed wrong. Nothing changes.) There may also have been an unwillingness in some quarters to put black people on television, which can’t have helped.

Ironically, it was a white, British music producer, John Schroeder, who was to prove instrumental in helping Cymande get as far as they did professionally before their first split. And, as the film suggests, it was multi-ethnic, musical movements of hip-hop and rap in the US that bought Cymande to more widespread attention there later. In that respect, Cymande were lucky; there are plenty of equally deserving musical acts who languish in obscurity to this day.

As for the suggestion that Cymande’s sound was completely unique, at least two other acts from around the same time were not dissimilar, neither of whom are mentioned in the documentary. Both came out of the US, so it would be true that they didn’t have to contend with British racism in any way, shape or form. However, the US hardly has a good record in terms of its treatment of non-whites – just look at the sidelining of US-Mexican singer-songwriter Rodriguez, the subject of Searching for Sugar Man (Malik Bendjelloul, 2012).

One similar act who predated the band was the heavily Latin-percussion-influenced Santana, formed in 1966 by the eponymous Mexican guitarist. Another formed at around the same time as Cymande, in 1969, was Little Feat, who similarly fused a cornucopia of different ethnic, musical styles and who, by the time they settled into a six-man line-up from 1972 onwards, were a multi-ethnic outfit. Not that either of these acts captured the attention of the 1970s New York club scene’s ears the way Cymande did, and not that either band was composed entirely of black people, as Cymande clearly were. And both were far more professionally successful than Cymande within a few years of getting started.

Cymande’s music, if like me you’re new to it, proves a revelation. Moreover, to their credit, they come across as humble and decent human beings, so spending 90 minutes in their company is no bad thing. And it’s fascinating to see how various other burgeoning movements in the US picked up their music and pushed it out into the wider musical culture, to the point where numerous people knew the music because of the recordings on which it was sampled, but few knew the name of the band originally playing it. This documentary helps right that particular wrong. If you are already familiar with their music, you’ll need no persuading to see this. If you’re coming in cold, as I did, be assured you’re in for a real find in terms of the band and a treat in terms of their music.

As well as the film itself, the upcoming Blu-ray contains unedited concert and other footage which appears in chopped up form in the documentary, plus an excellent interview by critic Jason Solomons with founding Cymande members Steve Scipio and Patrick Patterson which runs for over half an hour and covers a lot of interesting ground. Although they were beaten down by the system, it’s impressive that the pair are remarkably good-natured about the whole thing with no trace of bitterness, a similar feeling to the one you get from interview material with the six or so band members interviewed within the documentary itself.

Getting It Back: The Story of Cymande is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, February 16th and out on BFI Blu-ray, BFI Player Subscription, iTunes and Amazon Prime on Monday, 26 February.

Trailer: