Director – Ali Ray – 2025 – UK – Cert. U – 91m

*****

The origins of Impressionism are revealed via the 1874, anti-art-establishment exhibition which birthed what is today the world’s favourite art movement – out in UK cinemas from Tuesday, March 18th

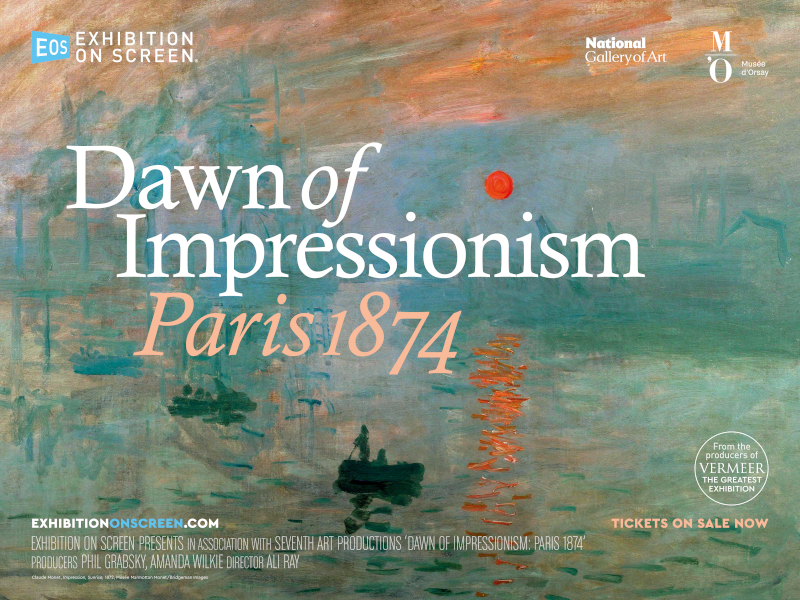

At the present time, the best known school of painting in the history of art must surely be Impressionism. To both open this latest Exhibition on Screen outing and promote the film on its posters, the filmmakers head to arguably the most iconic Impressionist painting of them all, Claude Monet’s Impression: Sunrise (1872), pictured above. To reinforce the point, a brief art auction sequence shows one of his paintings fetching astronomical prices.

Exhibition on Screen’s excellent, history of art documentary series entries are often built around one or more specific art exhibitions, and this one uses two as its foundation. The Musée d’Orsay in Paris held Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism from March 26th until July 14th 2024, after which the exhibition travelled to the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC to appear under the slightly different moniker Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment from September 8th 2024 until January 19th 2025. Alas, this is not one of those cases where your appetite will be whetted to go and see a current or upcoming exhibition, because both shows have already been and gone. It nevertheless provides a fascinating insight into how the school of painting now called the Impressionists came to be.

Before they became known as the Impressionists in 1874, these artists had a pretty tough time. “The dealers and collectors turned their backs on me,” said Monet. Édouard Manet added, “insults are streaming down on me like hail.” And Pissarro commented that he didn’t eat every day. Although a few art experts are visibly featured, notably the National Gallery of Art’s Mary Morton and the Musée d’Orsay’s Sylvie Ratry who were among thosse responsible for curating the exhibition, much of the commentary about the Impressionists and their historical context uses the words of the Impressionists themselves, and contemporary critics who wrote about them, all voiced by actors and tied together by helpful verbal narration. Little titles appear on the screen to tell the viewer whose words are being spoken, although at times towards the end it occasionally gets confusing as to which artist’s words are which.

In the Paris of 1874, there were two art exhibitions. One was the annual art establishment the Académie des Beaux-Arts’ show The Salon, the other was a self-realised show by some 31 artists who had, for the most part, increasingly been rejected by the Salon’s curators and who, in a bid to both exhibit their work and sell some of it to earn some a living, had formed the Société anonyme of artistes painters, sculptors, engravers, etc and set up their own rival show at the Boulevard des Capucines. The painters whose works filled the Salon would have their pictures crowded together on the walls; out of roughly 5 000 entries, around 2 000 were accepted. The place would be packed as punters elbowed their way to see the paintings. But it was as much about being seen as seeing.

Which artworks were accepted and which refused was down to a small committee of judges – incidentally all men – and had a great deal to do with the then French art world’s concept of good taste. Students at the French Royal Academy were given life classes drawing from male models in approved poses, and subjects based on classical scenes were encouraged. The writer and critic Émile Zola lambasted the judges for forcing artists to guess the taste of the judge in charge each year and produce work accordingly – as he caricatured it, one year green paintings were favoured, another year it would be blue or pink. From 1863, a Salon des Refusés was set up to show works of art that the Salon had rejected.

Artists who went against the Academy’s ideas included Claude Monet, whose Women in the Garden (1866) showed bright sunlight being cast onto the dresses of the women pictured. Zola saw such works as a breath of fresh air. “I would like to see some of these at the Salon,” he wrote, “but it seems the jury is there to carefully forbid them.”

Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe / Luncheon on the grass (c. 1862-3), shown in the 1863 Salon des Refusés, which depicts a nude woman and two fully clothed men in a park having a picnic, was derided as a bad picture or, worse, obscene. Zola sprang to its defence: “it is as if (a nude woman) had never appeared in a painting before.” Manet’s Olympia (1863), shown in the 1865 Salon, caused controversy because it’s portrayed nude was recognisably a prostitute.

In 1867, Manet held a show that was largely ignored by the public and at which he sold no work.

A small group of artists – notably Manet and Edgar Degas and their admirers Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley – started to hang out at the Nouvelle Athènes café in the Place Pigalle. At this point, the film goes through the major names, with a short section on each.

Manet was an aristocrat who liked to spend time with his impoverished artist friends. He never sold any paintings. There was a great rivalry between him and Degas

Monet spent his youth on the Normandy coast, inspired by the landscapes of plein air, marine artist Eugène Boudin. Monet had two seascapes accepted by the Salon, but then as he moved into plein air painting himself, found the Salon rejecting the newer, more challenging works. Manet described him as “the Raphael of Water”.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir came up through the Academy and initially painted according to its rules, just to prove he could. He was first rejected by the Salon in 1866. Camille Pissarro was the oldest of the group and, by accounts of the time, the kindest of them. His painting understood what has been described as the pathos of peasants. The poet and writer Armand Sylvestre said of them that Monet was the most skilful and daring, Sisley the most harmonious, and Pissarro the most direct and naive.

Manet tried to persuade the sole woman now recognised as one of the Impressionists, Berthe Morisot, to steer clear of them and pursue a career through the Salon, which was accepting her work. On visiting her studio and seeing The Mother and Sister of the Artist (c. 1869-70), he suggested finishing touches and added a few strokes himself.

Paul Cézanne was something of an outsider who was rarely in Paris. He tried not to imitate others, describing himself as the primitive of a new art. He had one work accepted by the Salon in 1862. Frédéric Bazille had a painting rejected by the Salon, so painted a Still Life with Fish in the Academy style, which promptly got accepted.

Under the heading Art for a New Age, the next section details how Monet, while living in London, made contact with art dealer Paul Ruand-Ruel who was taken with works such as Monet’s The Thames from Below Westminster (C. 1871), Monet’s Green Park, London (1871) and Pissarro’s The Crystal Palace (1871) enough to want to represent these painters and others like them in his gallery. He wrote that, “these paintings appalled my clients” as he found himself “doing battle with public taste.” Some 50 paintings in, with no sales, having provided a financial lifeline for those painters whose work he had bought, he refused to take any more.

The artists confronted this challenge by forming a Joint Stock Company to sell their work, renting space for an exhibition at the Boulevard des Capucines. “No-one has ever reconstructed what was in that exhibition,” says a clearly enthused Mary Morton, “all we had was a catalogue with no illustrations.”

Very little of the work shown was of the landscape type we now associate with the Impressionists. It was very much a multimedia show, featuring paintings, prints, watercolours, sculptures and enamels. Of the 31 artists included, only seven are known names today. Berthe Morisot was the only woman in the 31-strong group.

Her former teacher Joseph Guichard was appalled to see the “delicate work” of Morisot’s The Cradle (1872) side-by-side with Cézanne’s Modern Olympia (1873-4). “Manet was right in trying to prevent her from exhibiting,” he went on. Cézanne’s painting led the art critic M de Montifaud to describe him as a “madman in some sort of delirium”.

Renoir drew a mixture of praise and disdain from journalist Fernard de Gantès – he praised The Dancer (1874) for its lightness of touch but than laid into its vague background. Armand Silvestre thought that picture and The Parisienne (1874) nothing more than sketches, their treatment far too loose. Art critic Jean Prouvaire extols the virtues of Renoir’s The Theatre-Box (1874) with its blossoming, powerful lady.

De Gantès then takes on Edgar Degas’ The Dancing Class (1870), extolling its close study of real dancers. Philip Burty wrote about Degas’ The Ballet Rehearsal (1874) that “no-one can express with a surer hand the feeling of modern elegance”.

Shortly before this exhibition, the writer Charles Baudelaire published an essay calling on artists to stop looking to the past and instead look to the present and “the epic qualities of modern life”. As we hear these words, a print of a Paris cityscape gives way to moving film of Paris streets and their occupants.

Manet was the artist who responded to this call, says Mary Morton, citing Masked Ball at the Opera (1873) and The Railway (1873). The critics had a field day with the latter – it’s called The Railway, but where’s the train? Every good party needs a rabble rouser, says Morton, and that was Manet’s role. He exhibited at the Salon, rather than with the Impressionists, because he hadn’t been rejected and felt his voice would be more strongly heard there.

The Musée d’Orsay’s Anne Robbins, Curator of Paintings, and also of the Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism exhibition, explains that the Academy was under fire by 1874, and things were changing. Artists showing at the Salon were now trying to find subjects with which people could connect, according to Kimberly A. Jones, Curator, 19th Century French Paintings, National Gallery of Art. She cites Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Death of the Pharoah’s First Born Son (Salon, 1874) – a very precisely painted Biblical subject filled with lots of archaeological detail, visually lush – and then a closer look reveals a portrait of a father cradling the body of his dead son, perhaps resonating with a father in 1870 who had lost a son in battle.

For France, 1870-71 was l’année terrible (the terrible year) when the French had been at war with Prussia. One way of dealing with such trauma would be to move towards it, paint pictures of it, work out the pain. Another would be to move away and instead focus on elements which give joy or bring healing – joy, life, nature, colour, pleasure and beauty. Monet’s Boulevard des Capucines (1873), not just a bustling paris street but also, historically, the scene of great struggles in the Paris Commune (the revolutionary government for two months in 1871 following the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War). The joyous street scene dissolves into, in the words of art critic Ernest Chesneau, “an indecipherable chaos of palette scrapings.”

Alfred Sisley’s Apple Trees in Flower, Louveciennes (1873) might be seen as a painting of communion with the countryside in this context, much like the sort of images Pissarro (Hoarfrost, 1873) and Cézanne (The House of the Hanged Man, 1873) were painting at this time. But it’s an image of an area that had been decimated by the Prussian army during the recent conflict, with the post-war French government paying to plant seedlings alongside the few surviving apple trees; a painting of healing, regeneration and rebirth.

Only four painting were sold in the 1874 Impressionist’s exhibition. One of them was Monet’s Impression – Sunrise. It’s very sketchy,as the name implies, says Jones, . In a derisory and humorous review by Louis Leroire, there’s a sense of, how could the artist have signed something like this and presented it for public exhibition – it’s just a mess. Maybe we should just call these artists impressionists, meaning studiers or sketchers. After a couple of years, the artist have taken this negative word on board and used it to describe themselves, in that long tradition of groups appropriating insults hurled at them and turning them into badges of pride.

So, says Jones, we’re calling it the first Impressionists’ exhibition, but it really isn’t – it’s more about artists breaking with tradition and having more control over their output. And perhaps that’s the strange conundrum underlying this informative art documentary: it purports to be about a familiar art movement, but the reality of that movements roots turn out to be very different from much about that movement with which we’re familiar.

Exhibition on Screen: Dawn of Impressionism: Paris 1874 is out in cinemas in the UK from on Tuesday, March 18th. Check your local cinema for details, or click here.

Trailer: