Director – Hayao Miyazaki – 2001 – Japan – Cert. PG – 125m

****1/2

(A shorter version of this review was originally published in Third Way for UK release date 12/09/2002. At which point, hardly anyone in the UK outside of anime fandom knew who Miyazaki was.)

In director Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, a ten-year-old girl must survive a bathhouse run by demons after her parents are turned into pigs – back in UK cinemas from Thursday, December 26th 2024

To discover the films of Hayao Miyazaki – and those of his company Studio Ghibli (pronounced “Jib-Lee”) – is like suddenly being exposed to those of Disney without prior knowledge of their sheer number or quality. In Miyazaki’s native Japan, Spirited Away shattered box office records to succeed Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) as the most lucrative movie of all time. In the US, it won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature while making only modest inroads into the marketplace. Britain, however, is not the US, and it may well fare better here than it did there.

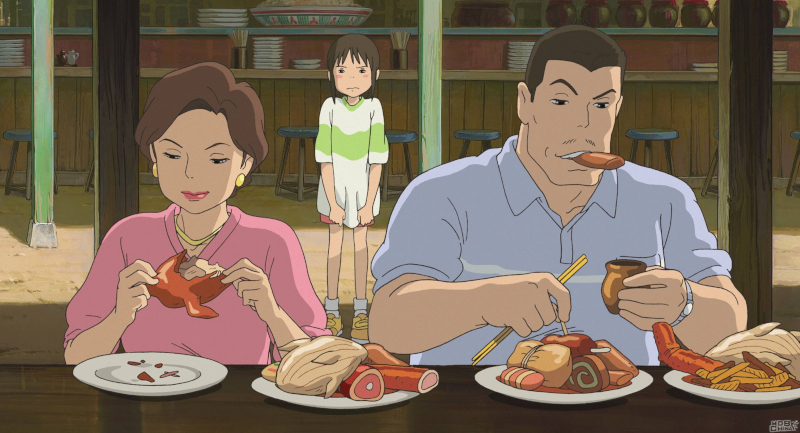

Previous Miyazaki outings have covered children’s experience of the countryside (My Neighbour Totoro, 1988; one of this writer’s favourite films of all time), a young girl’s learning to find her way in the world (Kiki’s Delivery Service, 1989) and conflicting loyalties among pilots in interwar Europe (Porco Rosso, 1992). Spirited Away shifts gear again with a tale of a ten-year-old girl who must survive the employment hierarchy of a bathhouse servicing minor demons and deities after her parents unwittingly wander into an abandoned amusement park, snack at an unhosted noodle stall and are turned into pigs by its grieved otherworldly clientele.

The quality of the animation, while stylistically Japanese rather than Western in its visual vocabulary, is superlative and a lush score by Miyazaki regular composer Joe Hisaishi (better known here for his soundtracks for director Takeshi Kitano) helps. The plot has a beginning (parents become pigs) and an end (they must be restored) but most of its running length is a meandering middle section; which renders the narrative construction somewhat problematic.

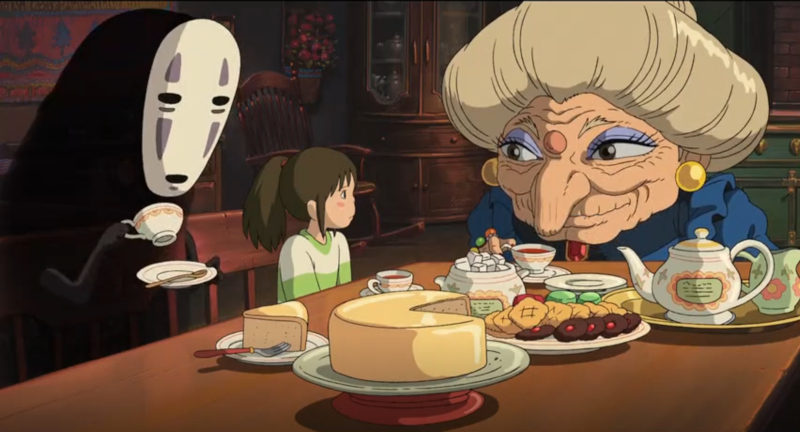

What seems to fascinate Miyazaki is the alternate hierarchy in which his heroine Chihiro must survive despite being an outsider – and he constructs it like a Japanese Alice In Wonderland environment, presided over by Duchess-like matriarch Yubaba with a twin sister, a giant infant and three hopping servant heads. Animism plays a key role with a pivotal episode in Chihiro’s past having her fall into a river and meet its spirit god. So too does the importance of naming, with Yubaba’s gaining power over her employees by magically stealing their names – the regaining of which by their rightful owners functions as a sort of redemption. Chihiro’s parents’ loss of humanity as they turn into pigs stands as an effective metaphor for all this.

Chihiro’s plight also has much in common with that of marginalized Dickensian child protagonists struggling to survive unjust social systems. When she is stuck with servicing a particularly dirty and smelly customer with whom no-one else wants to deal, the situation ultimately shifts to her advantage suggesting that charitable behaviour can bring its own reward. Conversely, a customer who offers gold to the staff proceeds to unceremoniously eat them once they take the money; but when Chihiro is offered the same coinage, she refuses to take it and her non-conformity with the prevailing greed affects the dire situation for the better. All of which suggests a great deal of common ground with Christian ethics for those who have ears to hear and eyes to see, although the film fairly obviously hails from a distinctly Japanese perspective rather than a Christendom-influenced Western one.

Westerners often assume animation to be a children’s medium, but Spirited Away shows that it ain’t necessarily so and struck a chord with Japanese viewers of all ages. While British children will be entranced by its otherworldliness, like Alice in Wonderland it might equally well be a neo-Dickensian tale for grown-ups exploring the nature of dreams and nightmares in great depth through the eyes of a child. If not Miyazaki’s greatest achievement by any means – Totoro, Kiki and Porco to name but three are all superior in this writer’s opinion – to the uninitiated, it provides a welcome introduction to the work of one of the cinema’s greatest living storytellers.

Spirited Away is back in UK cinemas from Thursday, December 26th 2024.

Spirited Away is now showing on Netflix (subtitled / dubbed) and can also be seen in the Anime season April / May 2022 at BFI Southbank (subtitled / dubbed for family screenings).

A shorter version of this review was originally published in Third Way for UK release date 12/09/2002.

July / August 2024 update: Spirited Away is currently the subject of a London staqe adaptation.

Trailer (original, subtitled, poor quality):

Trailer (subtitled, 2018):

Trailer (Disney – dubbed):

N.B.

The film was originally released in the UK in both Japanese prints with subtitles and American English dubbed prints – and in this particular instance both versions serve the film well. You’re advised to check with the cinema as to which version they’re showing if you have strong preferences either way.