Director – Robert Bresson – 1959 – France – Cert. PG – 76m

*****

Why is a man compelled to pursue acts of petty thievery – acclaimed, arresting, existential drama is out in cinemas on Friday, June 3rd

I have just rewatched Bresson’s classic and am still not entirely sure I have its measure. Perhaps that’s the thing about great works of art. Oh, to have seen it on its original release, had I been old enough, and watch it without the baggage of it being proclaimed a cinematic masterwork.

Words on the screen proclaim at the outset that this is not the thriller its title might suggest; it’s rather a study of a man who repeatedly commits crimes which is trying to understand why he would do that.

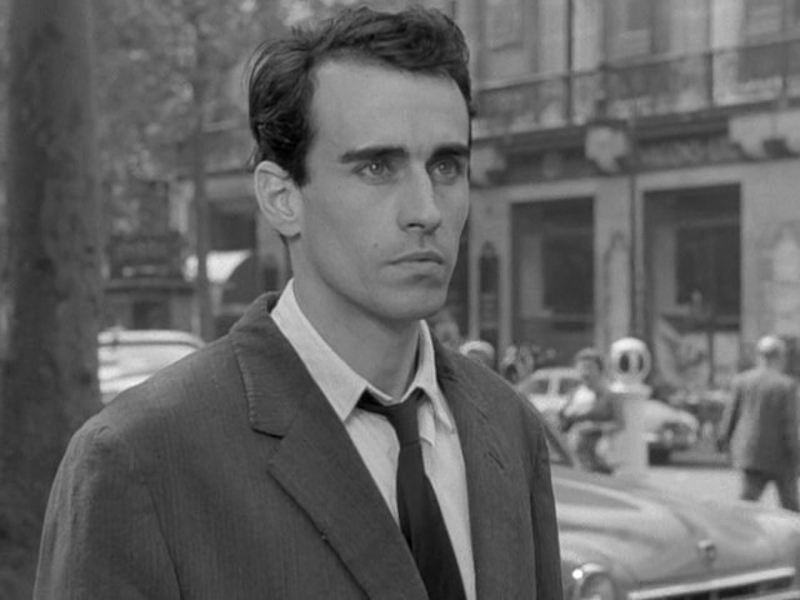

The characters, of whom the main protagonist Michel (Martin LaSalle) is the one who gets most screen time and indeed, is scarcely if ever off the scree, are played deadpan, with Bresson doing his utmost to ensure that his cast perform the roles without acting. He doesn’t want the actors’ craft to come between us and his images of people doing, being, talking. He seeks to avoid the artificiality of acting thereby allowing his performers to realise his images without any acting technique mediating them. Consequently, LaSalle walks through his role and doesn’t make us feel anything for his character. So too do the other actors in their lesser roles.

After the opening titles, the film which is set in Paris opens on a racetrack at the line of booths where people hand over betting money to bookies. Nothing abut the way the scene is shot is done for dramatic effect: you only have to compare the racetrack scenes in a heist movie from a few years earlier The Killing (Stanley Kubrick, 1956) where it’s all about building drama and tension. Bresson doesn’t have the slightest intention of doing anything like this. He opens on a character but it isn’t even his lead character, upon whom the camera takes a while to alight.

When the camera eventually finds Michel, the interest lies in following the development of an obsession. We might be watching either the first tentative act in a violent crime career or touch in a journey of sexual exploration but no, the film is called Pickpocket which Bresson uses to tell us what we’re going to see: a thief is going to take money off people without their knowing it. He stands behind an unsuspecting woman and, in an intercut close up of hand and handbag, oh so gently, oh so slowly removes a wad of notes, completing the act as offscreen horses, unseen by us but for their inescapable sound effect, gallop past him and the other, front-facing onlookers.

A large number of sequences carry a certain fascination for those of us not versed in the art of pickpocketing, which will be most viewers: we want to see how it’s done, and we also somehow want the perpetrator to get away with it. (In real life, no, but in the confines of a movie about a pickpocket, yes.) Yet Bresson doesn’t want this exactly: he wants to dispassionately observe the process and, towards the end of the narrative, possibly even for the perp to get caught.

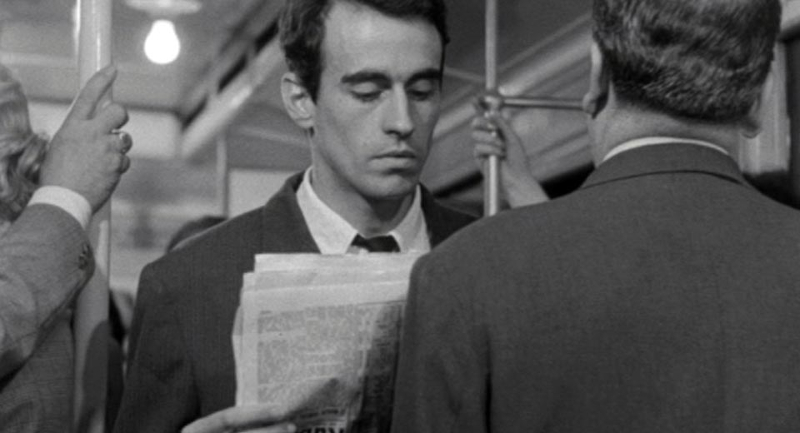

Perhaps there’s a problem here: Bresson hired real life pickpocket Kassagi as an advisor on the film, who also plays the thief who takes Michel under his wing and teaches him the tricks of his trade, and the close ups of hand or fingers entering purses, wallets or inside men’s jacket pockets, not to mention the scene of three men working together to fleece marks in a train station and on a train, are utterly compelling, almost as if these actions were the stars of the film (which, arguably, they are).

These scenes of pickpocketing are interspersed with deadpan drama of Michel’s life: his mother (from whom, we later learn, he has also stolen money) isn’t going to be around long, indeed, we attend her funeral. Prior to her death. She is befriended by attractive, young neighbour Jeanne (Marika Green) who after they’ve met often hangs out with both Michel and his friend Jacques (Pierre Leymarie). The latter disapproves of Michel’s criminal acts, and introduces him to his friend the police inspector (Jean Pélégri) with whom Michel discusses his personal theories about morality and crime (basically, a distillation of Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime And Punishment, wondering if some people are superior and should therefore be allowed to commit crimes with impunity, although no-one mentions this literary source in the film – and why should they?)

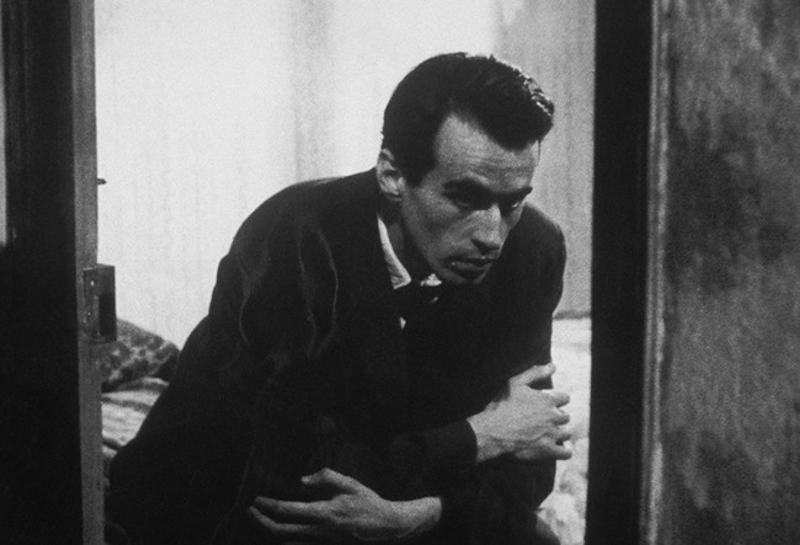

As Michel continues his criminal career, including a break for a tour round Europe and London for two years that on the screen is over so fast that if you blink you’ll miss it, Jeanne becomes increasingly important to his story. On his return, she is a single parent mum (thanks to Jacques, who she didn’t love enough to marry) and after he gets caught in the act of a theft at the racetrack, she visits him in prison where he falls in love with her, his feelings for her replacing his previous desire to steal. Normally, I wouldn’t give away an ending, but here. It doesn’t seem to matter: this may well be a film one will return to time and again, and the first time you see it it’s not really a shock when he gets caught, as it seems almost inevitable this will happen, just a question of when.

If the above sounds like a full description of the film, I feel I’ve only really touched the surface. Theirs an ordinariness about it that is deeply affecting to the viewer, and it asks questions about life, purpose, morality and God. (“I believed in him for about three minutes,” says Michel when the subject comes up.) Bresson was a Catholic and you can feel that world view in the very structure of his films.

In this film specifically, all that is somewhat undercut by the fascination of the almost documentary-like scenes of the pickpocketing acts themselves. These don’t occur elsewhere in Bresson’s work: they are unique to this film, which perhaps renders it problematic. BFI Southbank are currently running a season of his films through June, so that’s clearly a good opportunity to familiarise yourself with the wider Bresson canon should you so desire and place this one in context.

Or, you could just watch A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956) on BFI Player subscription while it’s available. To rehash a common interpretation. Pickpocket is about a man imprisoned (a compulsion to thieve) who finds liberation (through falling for a woman) at the end in prison, whereas A Man Escaped is about a man who escapes prison in order to be free.

Pickpocket is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, June 3rd. The season Of Sin and Salvation: The Cinema of Robert Bresson runs at BFI Southbank through June. A Man Escaped is on BFI Player.

Trailer: