Director – Michael Powell – 1960 – UK – Cert. 15 – 101m

*****

“It’s just a film – isn’t it?” The obsessive home moviemaker who lives in the attic is photographing women as he kills them, leaving an inexplicable look of abject terror on his victims’ faces as they die – plays one night only, Sunday, October 26th, 7.30pm, as part of Film Tottenham celebrates 100 years of community cinema, which runs until Sunday, December 7th 2025, now extended to Sunday, December 21st

More on Film Tottenham’s two current seasons below review.

Review originally written for 2023 UK cinema reissue on Friday, October 27th 2023 alongside major BFI season Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds Of Powell + Pressburger in late 2023

(Warning: may contain spoilers.)

What would have happened to Michael Powell if he and Emeric Pressburger had never met each other? Powell cut his teeth making ‘quota quickies’ in the 1930s British film industry: low budget films whose function was to ensure British talent got a chance in an international industry dominated by product from Hollywood. His final film before he and Pressburger began working together is the impressive The Edge Of The World (1937) about a remote Scottish island. One of his first after they went their separate artistic ways was Peeping Tom (1960), now widely regarded as his strongest solo outing.

It was made the same year Hitchcock released Psycho, but where that film about a psychopathic killer worked wonders for Hitch’s career in Hollywood, this one saw Powell vilified by contemporary British critics. However it has been re-evaluated in the years since.

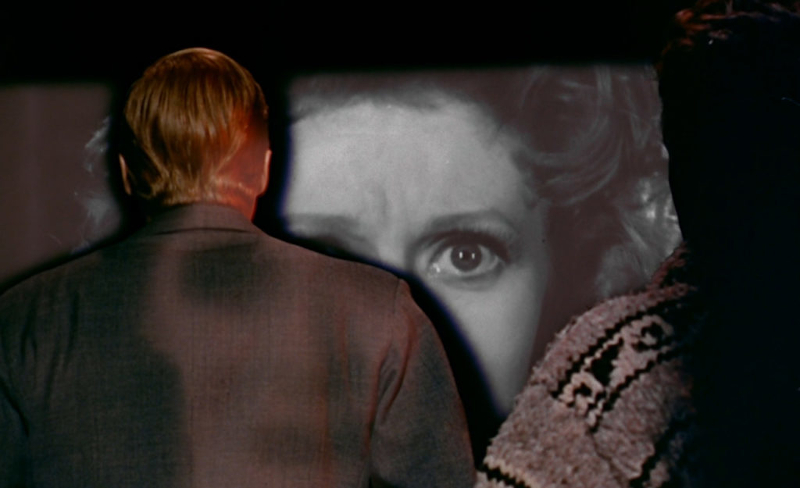

The plot concerns the reclusive Mark (Carl Boehm), a serial killer who films his female victims in an attempt to capture their fear on film as he does so. They die with a look of terror on their faces, and what drives the plot is, what did they see that was so frightening? (Somehow, I can’t imagine Pressburger alone or with Powell writing something like this; the whole basic, underlying idea seems nasty and callous – and that’s presumably why people reacted so badly to it at the time.)

Mark lives in the top floor of a huge house which, it later transpires, he owns. Here, he has his own darkroom facility for processing and projector for screening his home movies. On the lower floors live various tenants, among them on the ground floor are Helen (Anna Massey) and her blind mother (Maxine Audley). The outgoing and inquisitive Helen spots Mark in the corridor as he’s coming home one evening and invites him in to join her twenty-first birthday celebration, but he prefers to head on up to the attic and process the roll of film he’s shot earlier on the triple turret cine-camera he carries with him everywhere.

Nevertheless, she goes up later that same evening and the pair are clearly attracted to one another, although nothing physical takes place between them. He shows her a home movie film reel of his scientist father (played by director Powell) terrorising him as a boy by placing a lizard on his bedsheets, and of his dead mother’s funeral wake from the same period of his childhood.

By day, Mark has a job a focus puller at a film studio where a fairly lame looking comedy is being made. After hours, he has plans to shoot a little movie of his own, and ropes in hopeful extra Vivian (Moira Shearer from Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, 1948 and The Tales Of Hoffmann, 1951) who is unaware of his murderous, cinematic tendencies. After her body turns up in a trunk (opened by the hapless and not especially talented leading lady whilst shooting a scene), the police are called in. The narrative isn’t really interested in the police investigation, though, beyond the officers’ general bafflement as to why the corpses look so frightened.

Instead, the proceedings increasingly focus on Mark at home. He is visited by Helen’s mother, who wants to know more about the man who is a interested in her daughter. Because she’s blind, she can’t see any movies he might be playing on his home movie screen nor can she see whatever it was that terrified his previous victims. If he was thinking of murdering her too – and given that she is Helen’s mother one imagines he wouldn’t want to do so – her blindness protects her from him without her even realising it.

Finally, Mark is visited by Helen, who is horrified to discover his films of his victims’ deaths, railing at him with the immortal words, “It’s just a film – isn’t it?”

And that’s the point. Movies – and art – are all about artifice. They aren’t real. Just as The Red Shoes is about art being more important than anything else (Why do you want to dance?” Response: “Why do you want to live?”), so Peeping Tom is about someone obsessed with cameras and looking. “Scoptophilia – the morbid urge to gaze” as it’s described in the film. Helen, without seeing it in quite these terms, thinks there’s something unhealthy here (as do we, but then we’ve watched the murders through the camera – which viewpoint prevents us from seeing the cause of the victims’ deaths, ultimately only revealed to us when we look from a different vantage point than the viewfinder of the camera) and suggests Mark put down the camera she has never seen him without, so they can go out together without it being there.

There’s another issue lurking here too: men looking at women. Through cameras. With sexual overtones of capture, domination, possession, destruction. Fifteen years after Peeping Tom and Psycho, and the slew of largely US-made ‘slasher’ horror movies spawned by the highly successful and therefore high profile latter (but not the former, castigated on release and consigned to obscurity at this pre-home cinema period), Laura Mulvey would write her famous essay on The Male Gaze, codifying feminist film theory for the next half century. Peeping Tom clearly fits that idea, but men have been looking at women a long time – just look at Western Art since the Renaissance.

Mark, warped human being though he may be, is looking for a muse, an inspiration, trying to capture it in an artistic medium (moving picture film, in his case).

Powell has a fascination for the visual mechanics of cinema – recording of images by the camera, film processing, and exhibition to an audience who (unlike Helen’s blind mother) must be able to see the film to engage with it. Working with cinematographer Otto Heller (whose vast body of work includes The Queen Of Spades, 1949; The Ladykillers, 1955 and The Ipcress File, 1965) and art director Arthur Lawson (who previously worked on four Archers productions in that capacity starting with The Red Shoes), Powell covers the film in an extreme, lurid colour palette not unlike that of The Red Shoes to invoke the fantastique, the category under which I personally would file the film.

It benefits further by an extraordinary score credited to Brian Easdale (another Archers veteran from The Red Shoes and others), most notably the creepy, frenetic piano playing by Gordon Watson in the murder sequences and the moments leading up to them.

Everything takes place in claustrophobic settings: the opening murder of a whore in her room just off the narrow, covered Newman Passage (slightly to the North of London’s Tottenham Court Rd tube), a nearby stationer’s interior where hesitant punter Miles Malleson buys an album of “views” (pictures of women), the enclosed interiors of the film studio, its corridors, the house, its hallway, Helen and her mother’s flat, Mark’s darkroom and living quarters. Think of images in The Archers’ films and there are numerous wide exterior vistas, but there’s none of that here.

Its dramatic subject matter may be disturbing, indeed questionable, but – like The Red Shoes before it – as an essay about the obsessive nature of art and the hold it can have over its practitioners, the film is spot on. Powell’s best work may have been in collaboration with Pressburger, but in Peeping Tom (as in The Edge Of The World) he most definitely has something important to say and strains at the boundaries of what is possible in the medium of cinema in order to say it.

Peeping Tom plays one night only, Sunday, October 26th, 7.30pm, in Film Tottenham celebrates 100 years of community cinema which runs until Sunday, December 7th 2025, now extended to Sunday, December 21st.

*** Film Tottenham’s two current seasons ***

Love and Obsession (programme runs until Sunday, November 30th)

in conjection with major BFI season Too Much: Melodrama on Film

loveandobsession.eventbrite.co.uk

100 years of community cinema (programme runs until Sunday, December 7th), now extended to Sunday, December 21st

100yearsoffilm.eventbrite.co.uk

More Powell + Pressburger reviews.

Review originally written for 2023 UK cinema reissue on Friday, October 27th, 2023 alongside; major BFI season Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds Of Powell + Pressburger at BFI Southbank and on BFI Player from Monday, October 16th to the end of December 2023.

Trailer:

2023 Season Trailer: