Director – Marq Evans – 2021 – US – 96m

****

The rise and fall of stop-frame Claymation pioneer Will Vinton and the Portland, Oregon animation studio that bore his name – out on digital from Monday, November 21st

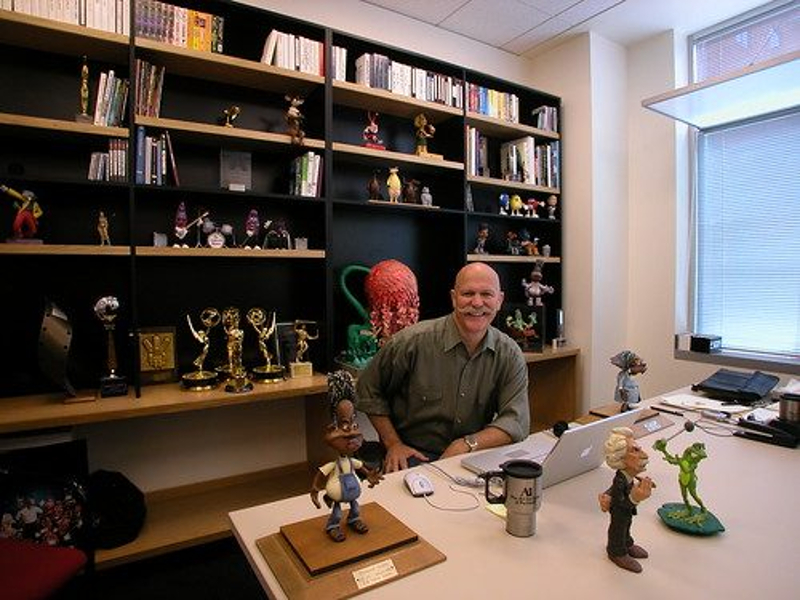

Will Vinton, founder of Will Vinton Studios and the man who made Claymation a US household name, is in the middle of legal proceedings between himself and Phil Knight, founder of multimillion shoe company Nike. How could these two very different individuals have come into contact with one another? Well, they had a number of things in common. Both were residents of Portland, Oregon who had built up businesses there based on a successful brand name.

In the sixties, while studying architecture at Berkeley, Vinton discovered Gaudi’s organic sculptured shapes which were to influence his animation work. Borrowing his dad’s 16mm camera, he started shooting anything and everything going on around campus. At an experimental film community he set up tabletop clay animation sessions, which would often turn out pornographic footage. He became fascinated by the magical process which imbued this material with life.

He built a studio in his house where in collaboration with artist and sculptor Bob Gardiner he made the short film Closed Mondays (1974) as an excuse to show off the techniques developed by the pair. The animated clay story of a drunk who enters an art gallery was rejected by Portland Film Festival but then started playing in other festivals and getting very good notices, eventually winning the Oscar for Best Animated Short.

As framed here, Gardiner was a gifted if undisciplined individual with an inability to follow projects through, whereas Vinton was the person who made things happen. “Will produced it”, says Vinton’s second wife Susan Shadburne of Closed Mondays. Vinton continued to run the studio, hiring staff on a permanent basis, while Gardiner went off to pursue other interests. As the studio produced short after short, Gardiner grew bitter feeling that Vinton was profiting off his techniques, vandalising the studio walls with graffiti overnight and issuing death threats to Vinton.

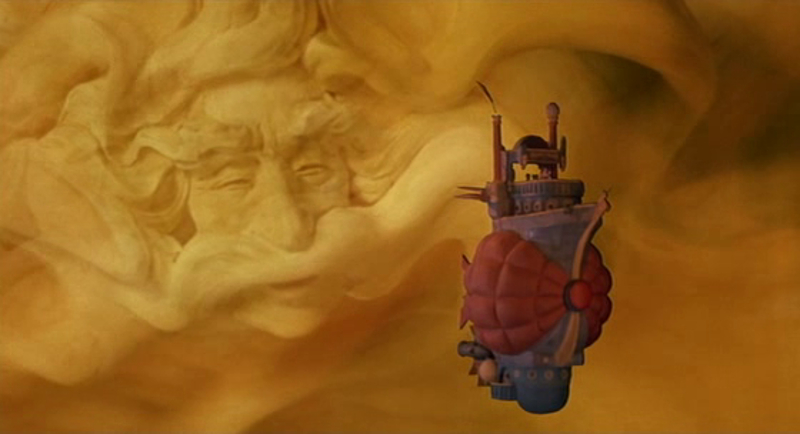

After such shorts as the Oscar-nominated Rip Van Winkle (1978) and The Great Cognito (1982), Vinton embarked on a feature The Adventures Of Mark Twain (1985). There are numerous comparisons of Vinton to Disney with him being viewed as the Disney of Claymation and a filmmaker with the unfortunate tendency to take all the credit for the numerous talented staff who worked on his films.

Claydream never mentions that the period in which Vinton was making his seminal shorts and first feature was the one of the Disney Studio’s decline following Walt’s death from its last great animated feature with his personal input The Jungle Book (1967) through to its eventual resurgence starting with The Great Mouse Detective (1986). The documentary does however detail the problems Mark Twain encountered with US distributors who failed to understand its subtleties and marketed it as a children’s movie moderated with Parental Advisory stickers which were to prove the kiss of death. That’s a travesty in this writer’s opinion, because the script by Susan Shadburne effectively exploits Mark Twain’s writing while the film does justice to Vinton’s claymation techniques. It deserved far better than its distributors gave it.

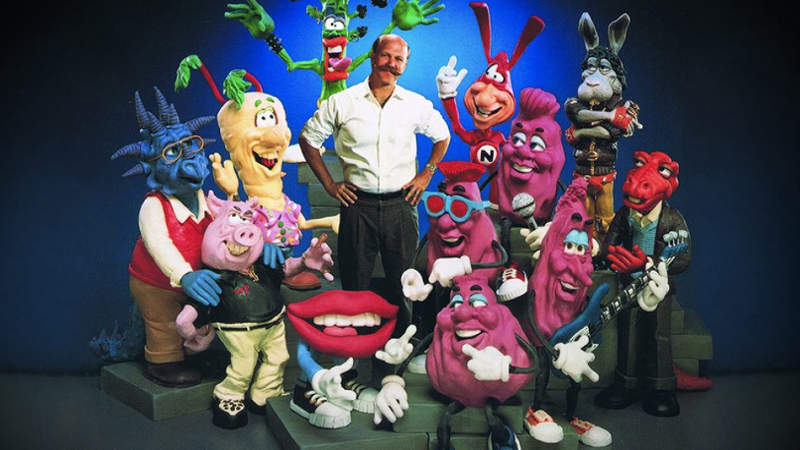

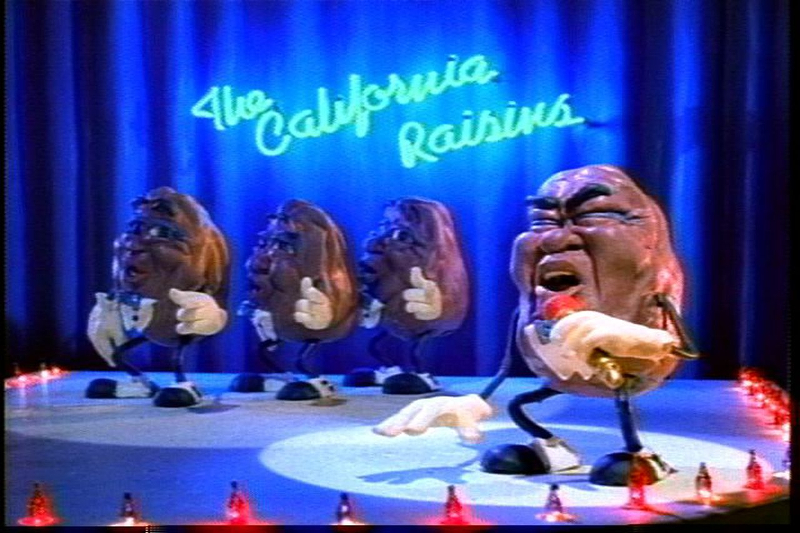

Vinton’s great commercial success soon followed, however, and from an unexpected quarter. His ad for the California Raisin Advisory Board featuring characters called the California Raisins went viral in a time before the internet when there was no real concept of going viral. A primetime TV special Meet The Raisins came in its wake, but where Disney as much by luck as by deliberate strategy had secured licensing deals on all his characters, Vinton failed to do this for the Raisins thus missing out on a huge potential slice of income for the Studio. As the years wore on, he attempted to tick more and more Disney boxes – licensable characters like Wilshire Pig, theme parks, Saturday morning TV shows in cel animation – but in doing so alienated his creative staff.

In 1998, Vinton sold 15% of the company to the financially savvy Phil Knight, who then set about buying shares from other shareholders. He also signed a contract enabling Knight to fire him for no reason at all, which Knight did after two lucrative TV series were cancelled, and several feature projects failed to reach fruition. On his initial involvement, Knight also secured an entry level staff position for his son Travis who would later run the company rebranded as Laika Studios after Vinton’s departure, producing and working on the animation of several impressive stop-frame features and even directing Kubo And The Two Strings (2016).

Vinton, meanwhile, refused to bear a grudge, worked on artistic projects outside of animation and was able to spend more time with his family who he had neglected through the busier years of his career. He was diagnosed with blood and bone cancer in 2006 and died in 2018.

Like Disney’s great rival in the 1930s Max Fleischer, who failed to make a move into sustainable, animated feature production and who like the Disney Studios’ decline immediately after Walt’s death isn’t mentioned in this documentary, Vinton’s life plays out here like that of a Walt Disney also-ran. In both cases, this is a great shame. No-one can take away Vinton’s remarkable achievements – the building of a highly innovative animation studio and a decade of truly groundbreaking shorts, culminating in The Adventures Of Mark Twain, which stand as a monument to his creative, technical and artistic animation genius. Sadly, he didn’t possess quite the business acumen to go with it, which, ultimately, is what let him down. This highly informative documentary provides a helpful guide as to how all that happened, making it a must-see for anyone interested in animation.

Claydream is out on digital from Monday, November 21st.

Trailer:

Festival Trailer:

Festivals

2021

Tribeca