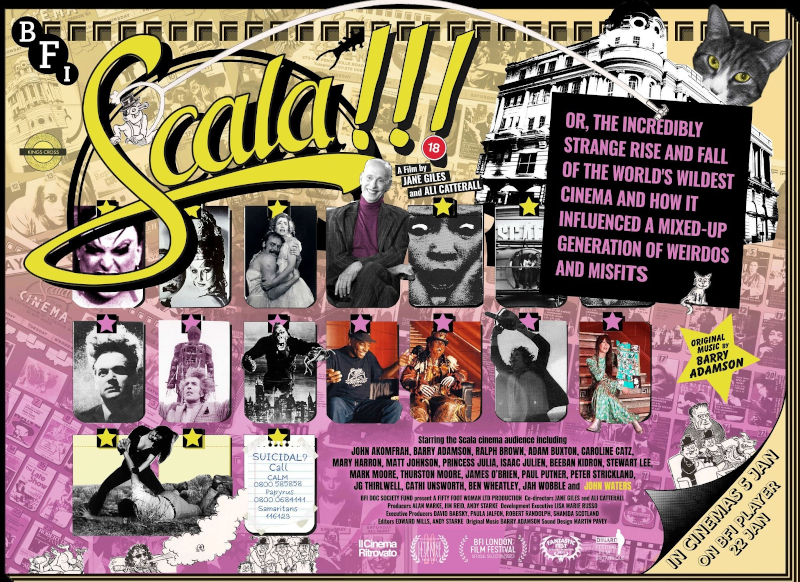

Directors – Ali Catterall, Jane Giles – 2023 – UK – Cert. 18 – 96m

*****

From 1978 to 1993, London’s Scala Cinema programmed everything from art house to sexploitation, ushering in the upcoming generation of anti-establishment musicians, filmmakers, and others – out in UK cinemas on Friday, January 5th

Whatever the strengths of this film – and they are legion – it may be impossible for me to write an objective review of it. From my first visit to Tottenham Street to watch an afternoon programme of back-to-back Tex Avery animation shorts on Saturday, 25th October 1980, I could often be found at London’s Scala cinema in the 1980s, broadening my mind as I lapped up welcome servings of movies long or short, old or new, highbrow or trashy. So there are a few additional titbits in what follows which come from my own personal, mental Scala archive of memory rather than from the documentary itself.

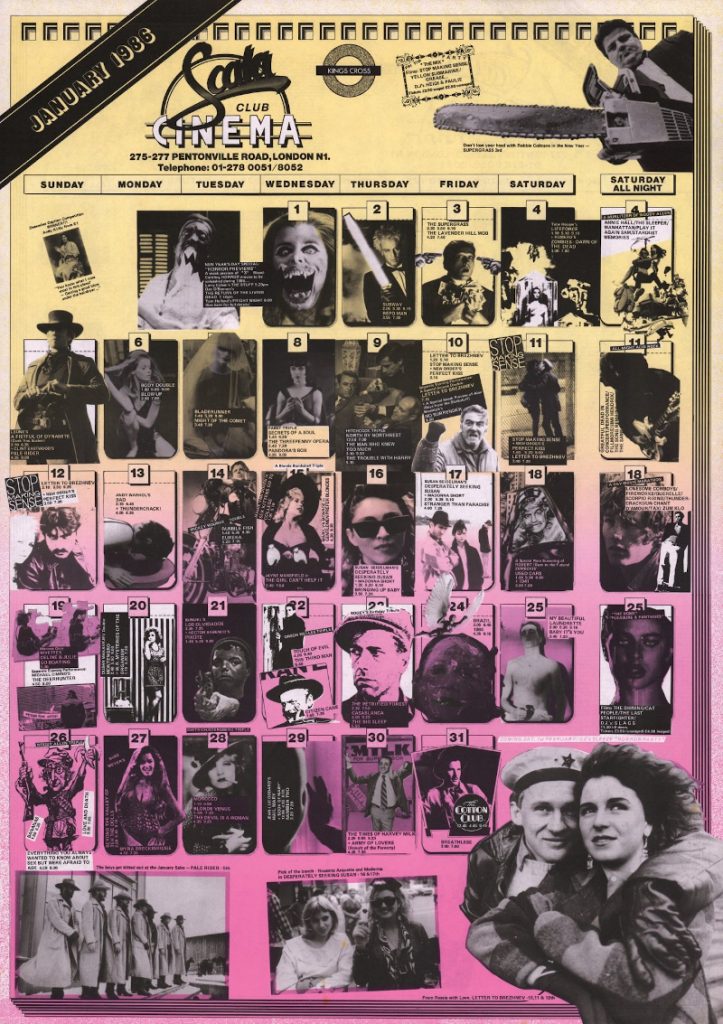

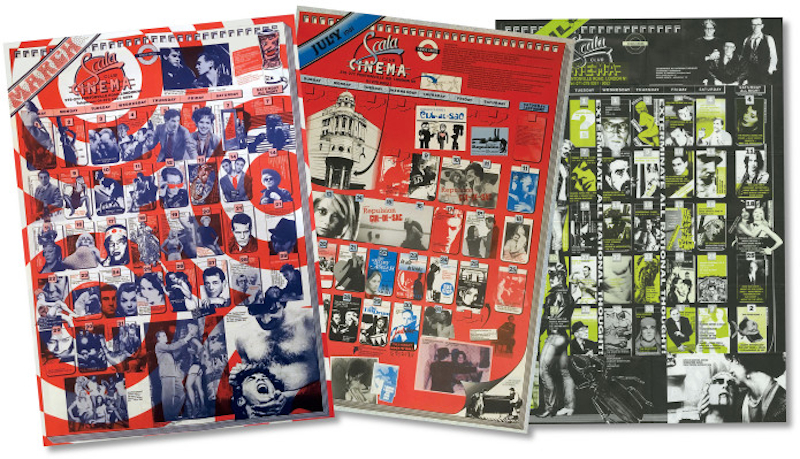

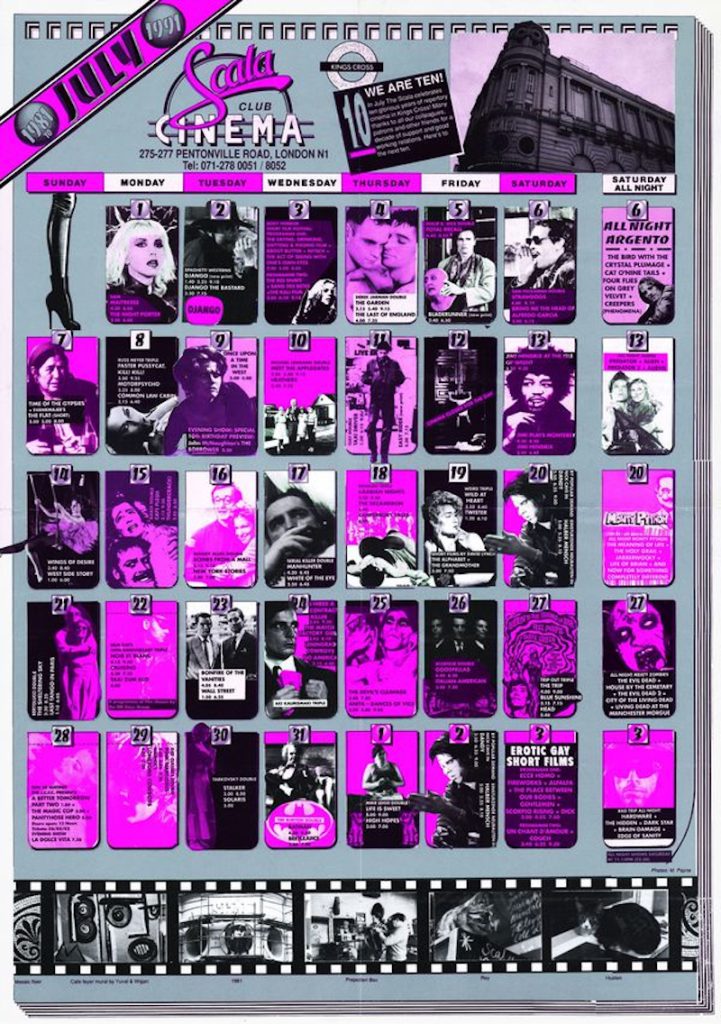

As for the date, my memory’s not actually that good. Such information can, however, be discerned from the wondrous if unfeasibly large-sized book SCALA CINEMA 1978-1993, which amongst other things contains all the monthly Scala programmes. It was written by co-director and former Scala employee / programmer Jane Giles’ and edited by fellow co-director Ali Catterall.

Back in the late 1970s, through the 1980s and into the early 1990s, the Scala was a cinema to be reckoned with. Its demise coincided with the rise of the early home video formats, not mentioned in this excellent if idiosyncratic documentary, and a court case which this covers towards the end of its running length.

This was a decade and a half when film was celluloid, film prints had sprocket holes for reels held momentarily in place on projector reel sprockets and the physical product could easily become caught or mangled within the projection machinery, or burn out when it got trapped for too long in the projector gate. That would happen from time to time at the Scala, from a period of UK cinema exhibition where cinemas generally weren’t particularly well maintained in the way they (arguably) tend to be today.

Even in that climate, though, the Scala stood out. The seats were not particularly comfortable, and the space immediately in front of the screen resembled a zoo’s monkey enclosure – a visual unrepresented here, although the legendary King’s Cross building’s short-lived, ten-month stint as interactive media natural history show The Primatarium is mentioned in a sporadic excursion into the history of the premises the Scala cinema took over in the early eighties, where on its first night it opened with a stop-frame / live action effects ape double bill of King Kong (Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack,1933) and Mighty Joe Young (Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1949), in keeping with the frontal environment.

Such double or triple bills were the staple diet of the radical programming, which included art house, genre, sexploitation, music films and other fare guaranteed to ground the regular attender in a wide and eclectic variety of cinema. In its earlier Tottenham Street days, a site it had to leave when the premises became the first home of Channel Four Television in 1981, it had opened in 1978 showing the distinctly weird US cult midnight movie success Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977).

Membership was an obligatory condition of entry, as it entailed a legal loophole whereby absolutely anything uncertificated could be screened on the premises without risk of prosecution by the British censor. Nothing would ever be cut for reasons of censorship, as was the case with many films going through the BBFC at this time, which earned the Scala immediate kudos among sexploitation and / or horror and / or other extreme cinema fans.

Its employee-programmers took great satisfaction in regularly showing movies that you couldn’t find screening anywhere else, such as the old dark house horror tropes hardcore porn mashup Thundercrack! (Curt McDowell, 1975), often storing on the premises – at least as legend had it – the only known print of the film which would become slightly more worn, battered or damaged with each physical journey through the premises’ twin projectors.

The place’s monthly programme posters were legendary, and would adorn many a kitchen or bedroom wall, only to be binned and replaced with the new one at the end of the month. (Alas, many of us wish we’d kept our copies for posterity.) Graphic designer Mike Leedham recounts how the first posters rigorously kept pictures and words within the frame allotted to each specific day, as per accepted, professional graphic design practice, but after a few months of chaos (and possibly also drugs), bits of image and copy would bleed outside the designated area. It didn’t help that something was always off in the colour separation process when the posters came back from the printers.

Once the Scala moved to King’s Cross, audiences could hear the rumble of tube trains passing beneath at regular intervals. It might not be quite the thing for today’s high-end cinema sound system fetishist, but it most definitely added to the character of the place and the richness (if that’s the right word) of the viewing and listening experience.

It was said that if you turned round and instead of the screen watched the audience, it could be even more exciting. Sometimes, people would be having sex in the back row. On one occasion, an audience member regaled everyone else present throughout the screening in a loud voice impossible not to hear detailing the ending of the movie (The Thing, John Carpenter, 1982). The lavatories were a constant bustle of activity; drugs were frequently taken.

King’s Cross at that time was something of a dodgy area, and the audiences for the Scala’s legendary all-night Saturday screenings would often include people who’d come in off the street for somewhere warm to sleep. Many people in these all-nighters would doze off in one film and wake up during the next one, and I personally can remember the most incredible feeling of euphoria having made it through five films and staggering out into the cold, early Sunday morning, King’s Cross air afterwards.

The Scala was known for its two cats, the aloof Huston and the more adventurous Roy. The latter would happily prowl around the seats in the dark. Nothing quite enhances the scare factor of a good horror movie like something hairy suddenly brushing past the back of your head as Roy walked gingerly along the backs of the seats in which engrossed punters were sat in the dark. The film mentions his walking along rows and brushing people’s feet, but that wasn’t what I remember most vividly.

There were special events – I can recall the cinema being visited for bills of their films by such cult figures as Hong Kong action star Chow Yun-fat or Italian giallo director Dario Argento – and, on at least one occasion, a surprise film presented in a double bill with If…. (Lindsay Anderson, 1968). The surprise film was A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971), banned in the UK by Kubrick until his death, and a successful lawsuit was filed on his behalf by distributor Warner Bros. against Jane Giles herself, a punter from age 17 who ran and programmed the Scala from age 23 between 1988 and 1992, for having screened it.

Financially, the Scala had run benefit screenings to raise money for radical causes, such as the Gay’s The Word LGBT+ bookshop, founded like the Scala itself in 1979 at the start of the Thatcher era, and unexpectedly raided by police one day in 1984. Its attempts to raise money to pay court costs incurred by the Clockwork Orange case were only successful up to a point, sadly failing to raise enough to keep the cinema itself open.

An extraordinary array of then current and future filmmakers and musicians passed through the Scala’s doors as either performers or punters. Back in 1972, it had hosted gigs by Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, which produced Mick Rock cover photos for the Transformer and Raw Power albums. If the Lou Reed gig seemed out of place, the Iggy Pop one has gone down as the stuff of legend.

Among those musicians who later attended the cinema as a punter as Barry Adamson (additional music on Lost Highway, David Lynch, 1997; Gas Food Lodging, Allison Anders, 1992), who talks here about the place’s effect on his Moss Side Story album, and who also composed the soundtrack for the current documentary. The THE’s Matt Johnson can be seen in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it clip.

Pope of Trash John Waters, whose films were regularly screened and who clearly took his Scala audiences to heart, is one of the best interview subjects, along with Shock Around the Clock horror festival’s effusive co-founder Alan Jones, and sharply-dressed sexploitation enthusiast David McGillivray.

One of the most memorable sequences has employee Ali Kayley describe her one experience when she imbibed drugs at work, resulting in an apparition of tentacled punters approaching the box office window, spectacularly and appropriately brought to life here in memorably garish and tacky stop-frame courtesy of animation director Osbert Parker.

Like the Scala itself, the film is a no-holds barred celebration of life, peppered with numerous clips of the many and amazing films that graced the silver screen of the Scala to the accompaniment of those rumbling underground trains. In retrospect, going to the Scala felt like dying for a brief time and going to heaven, and this engrossing documentary admirably succeeds in capturing that sentiment for its 96 minutes.

SCALA!!! Or, the incredibly strange rise and fall of the world’s wildest cinema and how it influenced a mixed-up generation of weirdos and misfits is out in cinemas in the UK on Friday, January 5th.

Trailer: